There was much ado over Greenspan's recent comments that there is a 33% chance the U.S. economy will enter into a recession later this year. The Fed seemed to be caught off guard by these comments, and Bernanke testified before Congress that The Fed was still concerned about inflation and the economy is in good shape. Why would Greenspan make such remarks?

We believe it is highly likely that Greenspan's forecast is based on probit models designed by The Fed. For those of you who aren't familiar with a probit model, we will look at the following definitions of probit. Wikipedia's definition is: "In statistics, a probit model is a popular specification of a generalized linear model, using the probit link function. Probit models were introduced by Chester Ittner Bliss. Because the response is a series of binomial results, the likelihood is often assumed to follow the binomial distribution." About Economics defines probit as: "An econometric model in which the dependent variable yi can be only one or zero, and the continuous independent variable xi are estimated in:

Pr(yi=1)=F(xi'b)

Here b is a parameter to be estimated, and F is the normal cdf. The logit model is the same but with a different cdf for F."

For those who still don't know what a probit model is, let's just say it is an econometric forecasting model. Probit models have been used by The Fed to forecast recessions. These models are based on the slope of the yield curve and have been very reliable in forecasting periods of economic weakness. When the 90 day T-Bill yields more than the 10 Year treasury bond, the model views this as a negative development for the economy. The chart below shows the history of the 10 Yr vs. the 90 Day T-Bill for the last 20 years.

Jonathan Wright from the Federal Reserve Board's Division of Monetary Affairs developed a probit model that measures the spread between the 3 month T-Bill yield and the 10 Year Treasury yield. It also looks at the general level of Fed Funds. He has written a working paper entitled "The Yield Curve and Predicting Recessions" which compares 4 different versions of the model. He concludes that measuring the spread between the 3 month T-Bill and the 10 Year Treasury as well as including the level of Fed Funds is the best of the 4 approaches for predicting recessions. The results of the model are shown below. The number at the right is the probability of a recession and the red areas show periods of economic weakness. As you can see, this model has had a very close correlation when predicting periods of economic weakness in the past without giving false signals.

Griffin Kubik, a securities firm in Chicago, replicated this model. The model is currently saying there is a better than 50% chance of a recession in the next 4 Quarters. We have seen other models projecting as high as a 95% chance of recession. Some of these other models are based on the spread between the 1 Year T-Bill and the 10 Year, without factoring in the general level of interest rates. Wright enhanced these earlier models by including Fed Funds as a proxy for interest rates. It seems likely that Greenspan is using some variation of one of these types of probit models. Perhaps he has enhanced Wright's model with some other variable. Although each of these models project different probabilities for a recession, they all agree that the longer The Fed keeps the yield curve inverted, the greater the probability our economy will enter a recession by the end of the year. The chart below shows the current estimation of the probability of a recession using Wright's model. Remember the probability was only at 20% when the chart above was created.

Thursday, March 29, 2007

Bonds: Probit Models Predict Probability Of Recession

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

4:36 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economy

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Taxes: The Battle Over AMT

It is estimated that the Alternative Minimum Tax, if left unchanged, will raise about $50 billion this year for the Federal Government. This is a tax implemented by Congress several years ago to make sure wealthy individuals pay their "fair share" of taxes. This tax was not indexed to inflation and is now affecting many members of the not-so-wealthy middle class. There is considerable ongoing debate about what to do about the AMT in Congress, because it is not fair to leave it as it is. The Republicans would like to either repeal the tax or mend it for another year. The Democrats would like to change the tax so that more of the tax is paid by the wealthy and eliminate the Republican tax cuts from 2001 and 2003,which are set to expire in 2010, as a way to pay for the AMT fix.

Congress has consistently over-estimated it's ability to implement a "fair" tax code, and under-estimated the impact on the American people and our economy of constantly changing the code. The Alternative Minimum Tax is a good example of why it is time for a change in how Congress views taxes. We believe the Government has proven it's inability to create a fair tax system. Instead, they should simplify the code and beef up the enforcement division of the IRS. A simpler tax code would help to narrow the tax gap and the AMT could be eliminated without having to fret over the $50 billion in lost revenues it generates this year.

The Wall Street Journal on March 21,2007 had an article discussing the current Tax Gap because of under-reporting of taxes due. This amount is estimated to be $345 billion. The table/chart below shows the composition of the tax gap and the decline in the number of IRS enforcement agents over the last 10 years.

We believe much of this under-reported income is caused by the complexity of the existing tax code. The first step for Congress should be to simplify the code. The current system of graduated brackets, deductions, and exceptions creates incentives for taxpayers to find ways around paying taxes. The more complicated we make our tax system, the more money falls through the cracks. For example, a flat tax with no deductions would be simple and easy to implement and enforce. Some may say that a flat tax would be unfair. Our answer to that is: "How fair is it that we are paying taxes and there are $345 billion of taxes owed that others aren't paying?"

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

7:09 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Taxes

Monday, March 26, 2007

Bonds: How Strong Is The Economy?

The Index of Leading Economic Indicators is showing potential economic weakness in the months ahead. The chart below shows the LEI for the last 15 years. The LEI peaked out in January 2006 at 139.1. The levels for February, which were just released, show a reading of 137.3. This index is a good indicator of economic strength over the next 4-6 months. The weakness in this indicator would suggest slower growth or weakness for the balance of 2007.

The LEI is composed of 10 different components. The different components are listed below with both their weighting in the index and their contribution to the last reading of LEI. The Conference Board releases this data about 3 weeks after the end of the previous month.

The LEI is composed of 10 different components. The different components are listed below with both their weighting in the index and their contribution to the last reading of LEI. The Conference Board releases this data about 3 weeks after the end of the previous month.

The largest contributors to the LEI are the Money Supply and the Factory Workweek. These 2 components account for about 60% of the value of the LEI. Recently, there has been much talk in the press about the housing market and whether the weakness in housing will drag down the rest of the economy. This sector of the economy is measured by Building Permits which accounts for only 2.7% of the LEI. However, most of the focus of economists and the press has been on housing. Now, their attention is moving to high defaults in sub-prime mortgages, and possible tightening of credit conditions for new home buyers.

Let's look at the LEI and some of the other components of the index. Last month, 5 of the 10 measures showed weakness in the economy. These measures were: the yield curve, vendor performance, initial jobless claims, consumer expectations, and building permits.

There is value in following the LEI and all of these components. The weakness in the index is not coming from only 1 sector of the economy (housing), but is shown in several of the individual measures of future economic growth. There are several economists calling for the economy to pick up later in the year. (These economists are obviously not paying attention to the LEI). We feel this is unlikely, and expect the economy to continue to slow. This should provide a favorable backdrop for bonds.

All data shown above is from the Conference Board which releases the Index of Leading Economic Indicators.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

7:41 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economy

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Taxes: Tax Freedom Day

This is the time of year to be thinking about taxes. We believe that each investor has a unique tax situation, and we are concerned about their marginal tax rates in the selection process of individual securities for their fixed income portfolios. We believe the last elections were a watershed event for tax rates, and that marginal tax rates are likely to rise in the future. This will probably make tax-free securities more attractive compared to taxable securities for some investors in the future.

The Tax Foundation publishes some interesting data about taxes and their impact on our daily lives. As a way to show how much of our income we pay in taxes, they created Tax Freedom Day. If we assume that we pay our taxes before we can use the rest of our earnings, this would be the day that we are "free" of paying taxes and the rest of our earnings go to us. The later in the year we reach Tax Freedom Day, the more time we are working for the government and the less time we are working for ourselves. This is a valuable way of measuring the bite that taxes are taking from our paychecks, and allows for comparisons over time. The chart below shows Tax Freedom Day for the last 27 years. The axis on the left shows the number of days it takes to get to Tax Freedom Day and the graph shows the results over time. We reached a high of about 123 days in 2000 and now are working about 116 days for the government.

How much do you pay in Federal taxes and how much do you pay in State & Local taxes? The chart below begins in 1900 and shows the number of days over time you work for each of these.

If you are wondering how many days you work to pay for your taxes compared to how many days you work to pay for housing, the chart below gives you the answer. We work 77 days to pay Federal taxes, 39 days to pay State & Local taxes, and 62 days to pay for housing and household operation. Federal taxes is the largest category.

You may also be wondering how the different taxes break down by type of tax. Below is a chart that shows the types of taxes. For example, out of the 77 days you work to pay for Federal taxes, 30 days go to pay for social programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

The amount of time you spend working for the government depends upon where you live. The chart below shows you will be working harder for the government if you live in New York than if you live in Montana. The states in dark blue mean that Tax Freedom Day occurs later in the year than the light blue and white states. We would encourage you to visit the website for the Tax Foundation for further information. We have provided a link to their website on our blog for your convenience.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

10:24 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Taxes

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

Muni Bonds: Why Buy Premium Coupons?

Premium Coupon Bonds Are Less Risky

Bonds purchased at par (a dollar price of 100) are considerably more risky than premium coupon bonds for three different reasons. First, the duration is greater for a par bond. Second, the reinvestment of interest earned has less of an impact on total return. Finally, in a rising rate environment, par bonds become subject to the Market Discount Rule more quickly.

Most investors purchase bonds as a way to dampen the volatility of their whole portfolio and to create a stream of income. Since the bond portfolio is used to reduce overall risk, it makes sense to reduce the risk taken in this conservative part of the portfolio whenever possible. The purchase of premium coupon bonds is a natural way for the fixed-income portfolio manager to reduce the risk for his investors.

An Example of Bond Cash Flows

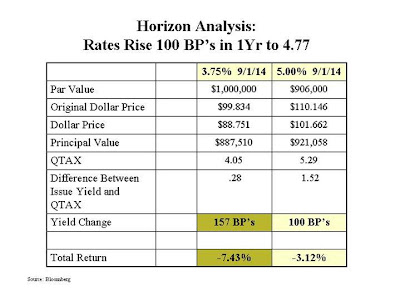

There was a Michigan Trunk muni bond issue that came the week of August 16, 2004 consisting of par bonds and premium bonds in the same maturities. The original pricing was the same for both coupon structures (3.77% yield). The par bonds were 3.75% due to mature on 9/1/14 and the premium bonds are 5.0% maturing on the same date. The following is a comparison of these two different coupon structures. Assume that about the same amount of money is invested in each bond. Both structures will provide about the same amount of total income or cash flows, if held to maturity.

The par bonds will consist of a greater par value of bonds ($1,000,000 vs. $906,000), but will have lower coupon payments than the premium bond ($375,000 vs. $453,000). The coupon payments are assumed to be reinvested at the purchase yield of 3.77%. The par bond will earn less reinvestment income than the premium bond ($73,395 vs. $91,078). Note: This illustration allows us to purchase a $906,000 block of bonds. Munis come in $5,000 denominations, but this example more accurately shows how the cash flows work.

Duration

The table shows the duration for the par bond is 8.248 at the time of issue. The duration for the 5.0% coupon is 7.927. Since the 5.0% coupon has the lower duration, it is the less risky of the two structures. Duration is a measure of market or interest rate risk. The greater the duration, the more market risk the investor is taking. Duration is similar to beta for stocks, where beta is the amount of risk the investor is taking compared to the risk of the market. One way to think of duration is as a measure of how much the price of an individual bond would change with a 1% change in interest rates. A bond with a duration of 4.0 would have a price change of about 4.0%. In our example, the par bond would change .321% more than the premium bond because of market risk (8.248-7.927).

Reinvestment of Interest Earned

The premium bond receives more cash flows from coupon payments ($453,000 vs. $375,000). The reinvestment of these cash flows creates additional interest earned for the investor. Since the cash flows received from coupon payments are greater for the premium bond, the amount of interest earned from reinvestment is also greater. In this example, we assume the reinvestment rate rises 1.0% to 4.77. This creates $4,479 in additional income for the investor in the premium bonds. This is a favorable characteristic in a rising rate environment. The investor is receiving his money back more quickly which allows him to reinvest it at higher rates (if rates rise).

Market Discount Rule

Avoiding the Market Discount Rule is the most important reason to invest in premium coupon bonds. The Market Discount Rule assigns a price (yield) for each security when it is purchased. If yields rise above that pre-assigned yield, the market would penalize the investor's security if the investor needed to sell the bond because the difference between the purchase price for the new investor and the price he receives at maturity would be taxed as ordinary income. This has a very negative impact on an individual security’s value. Most investors purchase muni bonds because they want tax-free income. Discount bonds cheaper than the market cut-off price will need to appeal to an investor willing to earn taxable ordinary income which is (in the case of the high net worth individual) most likely taxed at the maximum tax rate. Our example shows that the par bond has a market cut-off or QTAX of 4.05. If market yields were to rise to 4.77% for this maturity, the par bond would likely have to trade at a yield of 5.34% in order to entice investors to purchase the bonds. This extra yield is necessary because the difference between the purchase price of $88.751 and the price received at maturity (par or 100) is taxed at the taxpayers ordinary income tax-rate.

The premium bond would avoid this Market Discount Rule problem and would decline in value by (3.12%) vs. the decline in value of the par bond by (7.43%).

As you can see, the Market Discount Rule can have a very significant impact on total returns in a rising rate environment.

Who Buys Par Bonds?

The primary purchasers of par bonds are bank trust departments and individuals. Bank trust departments buy par bonds because of the nature of the trust relationship. In every trust, there is an income beneficiary and a remainder man. It is the trustee’s responsibility to make sure both parties are treated fairly. Tradition has argued that the best way to ensure fairness is to purchase par bonds. Remember that a bond consists of a series of cash flows. If a premium coupon bond is purchased and all of the income received is paid out, the remainder is less than what the remainder man would ordinarily be entitled to (part of the income is really amortized premium or principal). One has to question this logic, however. Is the remainder man of the trust being treated fairly if the market value of his holdings declines because of the market discount rule? One could argue that the trust department could still buy premium bonds and only pay out that portion to which the income beneficiary is entitled. This approach requires more work for the trust department, but is a lower risk strategy for the trust as a whole.

Retail investors or individuals typically purchase par bonds because they don’t understand how bonds work and they may not have the tools necessary to analyze bond cash flows properly. Bond risks are difficult to measure and not readily understood by many retail investors.

Conclusion

Risk management is a major component of managing a municipal bond portfolio. This example shows that premium coupon bonds are less risky than par bonds because they have less market risk, reinvestment risk is lower in a rising rate environment, and the risk associated with bonds becoming subject to the Market Discount Rule is greater for par bonds.

These are the reasons that most institutions and other savvy investors have been attracted to investing in premium coupon municipal bonds.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

3:09 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Munis

Monday, March 19, 2007

Bonds: Tax-Free, Taxable, Or Both?

The Problem

Perhaps one of the most confusing decisions facing an investment advisor today is whether some clients with taxable accounts should purchase taxable or tax exempt bonds for their high quality bond portfolios. This decision is straightforward for clients that earn large amounts of taxable income (over $326,450) which puts them into the maximum tax bracket of 35%. Municipal bonds are clearly the most appropriate investment for them. However, this decision is much more difficult when the client has invest able funds of $1-$3 million and very little (if any) taxable income coming from other sources. In these cases, the investment chosen “drives” the amount of taxable income that the client earns as well as their marginal tax bracket. For example, assume the client has an investment portfolio of $3.5 million and taxable income of $100,000. The portion the advisor allocates to the high quality bond portfolio is $800,000. Most advisors struggle with the appropriate mix of bonds for these clients. “Should I buy taxable bonds, tax exempt bonds, or perhaps a mix of both?” What is the proper way to make this investment decision?

Interest rates are constantly changing and so is the relationship between taxable and tax exempt securities along the yield curve. The changes in both interest rates and the inter-market relationships are important factors in the decision making process. The combination of changing rate levels as well as changing income levels makes this decision appear to be challenging.

Marginal Tax Rates

Tax-managing bond portfolios begins with a careful examination of the client’s marginal tax rate. This rate will determine the suitability of different fixed income securities for each client. This rate is dependent on the type of filing of the taxpayer and the level of income the client earns after all deductions are subtracted.

Filing Status

A single person has a higher marginal tax rate for the same level of income than a married person filing a joint return.

Income

We are referring to taxable income after all allowable deductions have been taken. This is the number from line 43 of the 1040 return. This income number can be used to determine the client’s marginal tax rate. Securities available in the tax-exempt and taxable markets can then be compared on an after-tax basis. These after-tax rates are then compared by maturity to determine what works best for each client. These rates and relationships are changing on a daily basis. Frequently, the portfolio is optimized by using a combination of longer maturity munis and shorter maturity agencies.

More emphasis needs to be placed on determining each client’s marginal tax rate. This may be difficult because of the many variables involved which causes this rate to be a “moving target.” Superior bond portfolio performance depends on improving this process.

Ratio of Munis to Agencies

The muni yield curve can be compared to the taxable yield curve to determine the percentage that each of the maturities trade compared to taxables. Munis traditionally trade at lower ratios in the shorter maturities and higher ratios in the longer maturities. The chart below shows the historical ratio of a 10 year muni compared to a 10 year U.S. Treasury bond. The average for the last 3 years is 86%. Recently, this ratio has fallen to 82.4%. This has an impact on after-tax yields and means that an investor needs to be in a higher tax bracket (86%-82.4%=3.6%) for munis to be attractive. This change is about equal to the amount of state tax a married person filing jointly would pay in the state of Arizona.

One way of looking at the current value of a muni compared to a taxable security is to take the ratio (munis/taxable's) and subtract it from 1. We can do this for all maturities along the curve and we get a chart like the one titled Muni/Agency Ratio which shows tax efficiency below. If we compare this graph to the client’s marginal tax rate (the blue line), we can see that munis will be attractive to the investor whenever this ratio is lower than the marginal tax rate. Munis are only attractive to this investor when he begins to look at maturities in the 5 year part of the curve. Munis would be attractive to all investors in the 35% bracket or higher. The advantage of this approach is that the tax-free/taxable ratio is constantly changing. We can monitor the ratios up and down the yield curve and compare them to the client’s marginal tax rate to determine which fixed income security is best suited for his/her needs.

Conclusion

Each individual investor has a unique tax situation. Returns may be optimized when more attention is paid to the marginal tax rate of each client. This requires familiarity with the client's tax return, and an understanding of the client's tax situation.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

9:36 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Taxes

Saturday, March 17, 2007

So You Think You Want To Be A Credit Analyst: Unfunded Pension Liabilities

Recently, S&P released a report entitled "Improved U.S. State Pension Funding Levels Could Be On The Horizon." This report is based on 2005 year-end data, which is the most recent data available for all states. S&P made the case that most state pension funds use 5 Yr smoothed returns, and the returns from 2001-2002 have been acting as a drag on the actuarial value of fund assets. If the equity market behaves itself, the 5 Yr smoothed value of these assets will increase as the returns from 2001-2002 fall off the 5 Yr averages. This increase in asset values will increase the funding of these state pension systems, which will help alleviate the current levels of underfunding. We are in agreement with this conclusion; however, there are some states that are grossly underfunded. Let's take a look at these state retirement plans and see how municipal credits are analyzed.

The chart below shows the 10 states with the largest Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liabilities (UAAL). California, at $47 billion, has the largest unfunded liability, Illinois is next with $31 billion, and Ohio is right behind with $30 billion. The rest of the top 10 are all under $15 billion.

While it is interesting to know the magnitude of the funding gap, it is beneficial to look at the percentage that is funded to determine the progress the state has made in providing money for these obligations. The chart below is based on data from the same S&P report as above. This chart ranks states by the percentage of the funding. West Virginia has the lowest value at only 47% funded, next is Oklahoma at 57%, and Connecticut at 58%.

While it is interesting to know the magnitude of the funding gap, it is beneficial to look at the percentage that is funded to determine the progress the state has made in providing money for these obligations. The chart below is based on data from the same S&P report as above. This chart ranks states by the percentage of the funding. West Virginia has the lowest value at only 47% funded, next is Oklahoma at 57%, and Connecticut at 58%. We now have charts that show the magnitude of the shortfall and the progress each state has made in achieving their goal of funding these pension obligations. It is also important to see how well these states can afford to meet these pension obligations. The amount of debt each state has outstanding can be calculated. If we divide this number by the population of the state, we arrive at a number for Debt Per Capita. Let's take the amount of the unfunded liability and divide it by the population to arrive at the Per Capita Unfunded Liability. When these 2 numbers are combined, we have a measure that is a better representation of the total obligation of the state. There are also Per Capita income numbers available for each state. These numbers show the earning power of the average person in the state. The combined Debt Per Capita numbers divided by the Per Capita income number gives us the percent of debt to income for each person. This number helps to show how significant the debt burden is for taxpayers in any given state. The chart below shows these numbers for the 10 states with the highest combined debt burden compared to their earning power. All 10 states have 10% or more ratios, with Alaska over 20%.

We now have charts that show the magnitude of the shortfall and the progress each state has made in achieving their goal of funding these pension obligations. It is also important to see how well these states can afford to meet these pension obligations. The amount of debt each state has outstanding can be calculated. If we divide this number by the population of the state, we arrive at a number for Debt Per Capita. Let's take the amount of the unfunded liability and divide it by the population to arrive at the Per Capita Unfunded Liability. When these 2 numbers are combined, we have a measure that is a better representation of the total obligation of the state. There are also Per Capita income numbers available for each state. These numbers show the earning power of the average person in the state. The combined Debt Per Capita numbers divided by the Per Capita income number gives us the percent of debt to income for each person. This number helps to show how significant the debt burden is for taxpayers in any given state. The chart below shows these numbers for the 10 states with the highest combined debt burden compared to their earning power. All 10 states have 10% or more ratios, with Alaska over 20%.  This may be easier to understand if we use some actual numbers. Let's use Alaska as an example. The Debt Per Capita (PC) is $2,000 and the Unfunded Pension Liability is $6,212 PC. This is a total of $8,212 PC divided by the PC Income of $35,612 to give us a debt ratio of 23%. This is a big number and should cause concern in some investors. This measure gives us a better idea of Alaska's financial health than the $2,000 Debt Per Capita number.

This may be easier to understand if we use some actual numbers. Let's use Alaska as an example. The Debt Per Capita (PC) is $2,000 and the Unfunded Pension Liability is $6,212 PC. This is a total of $8,212 PC divided by the PC Income of $35,612 to give us a debt ratio of 23%. This is a big number and should cause concern in some investors. This measure gives us a better idea of Alaska's financial health than the $2,000 Debt Per Capita number.

These numbers do not include OPEB liabilities. OPEB is Other Post Employment Benefits and is primarily the actuarial accrued liability for health care costs. States will be coming out with these numbers over the next 3 years as required by GASB 45. This is another huge liability that municipalities have incurred. It should be important to each investor to look at not only traditional numbers such as Debt Per Capita, but also to include unfunded pension liabilites and OPEB obligations in their analysis to determine the creditworthiness of each security. So, do you still think you want to be a credit analyst?

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

12:15 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Credit

Friday, March 16, 2007

Bonds and the Fed

We have never had more confidence in the Fed and it's ability to manage the economy. Yet, the Fed has a history of creating excessive credit conditions, and then taking steps to remove these excesses. Tight money tends to cause distress first in the areas that are most overextended. The chart below is from David Rosenberg at Merrill Lynch. His theory is that when the Fed is in a tightening mode, they will continue reigning in credit until something bad happens. Then they will ease to counteract the damage they have just done, and the cycle repeats itself. Some of the most memorable examples from Merrill's chart are, the Tech Wreck, Long Term Capital, S&L Crisis, and Penn Square Bank. Many of these negative events were a result of the excessive credit conditions the Fed created in the first place. When they took steps to get the market to return to normalcy, "bad things happened."

One might ask why this pattern tends to repeat itself? This is largely the result of the Fed trying to manage the economy. Their tool of choice is to control the process of "borrowing short and lending long". In essence, this is how our banking industry works, and it is a great system. When the Fed lowers short-term rates, they make the yield curve steeper. This allows banks to make a larger spread (profitability) and over time increases the amount of liquidity that is available in the credit markets. This increased availability of credit allows borrowers to have the funds that are necessary to make purchases, which in turn stimulates the economy. The reverse is also true when they raise short-term rates which drains liquidity from the system. Isn't it interesting that our system depends upon the borrowers to get it going and to slow it down?

After 9/11 there was a massive reduction in short-term rates which produced large amounts of liquidity and availability of credit. Much of this money went into the housing market. Many of those loans were financed with little or no money down, and many of the borrowers were sub-prime borrowers. It wasn't that long ago that the public and economists were thinking that higher rates wouldn't have that much of an impact on the housing market. Then they were saying that the housing slowdown wouldn't affect the economy and it would continue to grow, and activity would pick up later in the year. Now we are seeing high defaults in sub-prime mortgages by the people who couldn't afford the houses they were buying in the first place. So, will the sub-prime problem spread to the rest of the economy? That is the question being asked now. Shouldn't the question be: Why wouldn't we experience ripples across the credit markets? After all, the Fed has made money tight and we know from experience that they will continue in this mode until something bad happens.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

5:47 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economy

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Muni Bonds: Texas Says No To OPEB Rules

"Whoa!" says Texas to the new reporting guidelines for disclosing OPEB liabilities. The state treasurer, Susan Combs, recently stated that Texas was not planning to comply with the GASB 45 guidelines in disclosing unfunded Health Care liabilities for public workers. These guidelines, which are being phased in over the next 3 years, are designed to increase disclosure of unfunded liabilities so investors have a better understanding of the financial position of a municipality before investing in it's debt obligations.

The State of Texas is taking the following position relative to these disclosure requirements:

1. These are not "hard liabilities" of the State, because the legislature can change the amount it appropriates for the payment of these benefits.

2. It is impossible to know what this stream of benefits may be for the next 30 years.

3. Workers will suffer because municipalities will discontinue offering these benefits to their workers.

This is a very interesting approach to the OPEB disclosure requirements, because what the State is saying in plain English is this: "You can't make us do this because we don't really owe these workers these benefits, it's too much trouble to figure them out even if we did owe it to them, and how dare you jeopardize their future benefits (that we feel we don't owe them anyway)."

This is a unique response and has some serious consequences. First, it is a politically untenable position to take in regard to the employees of the State. After all, if you were an employee of the State of Texas, how secure would you feel your Health Care benefits were after you retired? Second, it is an attempt by the State to thumb it's nose at the GASB and investors. When Texas attempts to fund projects in the municipal bond market, it will receive an adverse determination letter for lack of proper disclosure. What investor will buy Texas' securities under those circumstances?

This position is indefensible and not reasoned properly. Estimates of the State's unfunded OPEB liability are around $50 billion. Can this be what is driving this decision by Susan Combs?

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

8:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Credit

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Bonds: The Economy

The level of interest rates is driven largely by long term inflationary expectations and the growth rate of the economy. We monitor the GDP Core price index as a measure of inflation, and the Index of Leading Economic Indicators (LEI), looking for clues about future economic growth. The LEI consists of 10 different economic indicators.

Let's take a look at inflation. There has been much talk about inflation in the press. We believe we have experienced a cyclical upturn in inflation, but the long term secular trend in inflation is still lower. The response from the Fed during the last 2.5 years has increased our confidence in both their ability and their desire to control inflation. The chart below shows the GDP Personal Consumption Core Price Index from 1992 to 2006. Also graphed on the chart is a 13 quarter moving average, which shows the smoothing of the index over a three year period. Bernanke has said that he would like to see this index under 2% as an upper band. It is currently 1.9%.

Economic growth depends largely upon the availability of credit. A good measure of the tightness of credit is the slope of the yield curve. Our economy has had an inverted yield curve since last June. An inverted curve is like a tourniquet on the economy. The lifeblood of the economy is money, and the Fed is restricting the ability of different sectors to have access to credit. The economy is gradually showing signs of weakness as the restriction of the "blood flow" to the economy affects different "body parts" more quickly than others. The chart below is for the interest rate spread between a 10 year treasury and fed funds. It shows the dramatic change in the yield curve that has taken place since the Fed began tightening in June of 2004. Banks are in the business of borrowing "short" and lending "long". When the yield curve is inverse, the economic incentive for them to loan money is reduced because they can't make money off the trade of borrowing short and lending long. This also helps to restrict the availability of credit, and helps to dampen the economy.

Perhaps the first body part to experience distress was housing. The weakness in housing is illustrated by the rapid decline in building permits which began their decline in the last quarter of 2005.

New orders for consumer goods are also showing weakness. This component in the index of leading economic indicators is an inflation adjusted value of manufacturers new orders for consumer goods and materials, and is designed to lead changes in production. This index peaked out in the middle of 2004 when the Fed began tightening credit.

The weakness in housing is now spreading to sub-prime mortgages. There is weakness in risk assets such as domestic and foreign equities, and in commodities like gold and oil. The question being asked now is, "will this weakness spread to other areas of the credit markets?" The answer is clear. The economy will continue to slow until the Fed realizes that it is about to kill the patient, and then they will ease up on rates to try to get things going again. This is a very favorable environment for bonds. We believe that current bond rates are attractive, and investors who are still bearish should rethink their positions.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

9:07 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Economy

Monday, March 12, 2007

Muni Bonds: Tax Reporting For Premium Bonds

How To Determine Reportable Tax-Free Income For The Investor

The amount of reportable tax-free income that an investor receives from their municipal bonds may be dependent on the investor’s cost basis in the individual security and the coupon structure of the bond. Many investors mistakenly believe that the coupon received from a muni bond represents their reportable tax-free income to be filed on line 8b of their 1040 tax form. However, this is only the case for all muni bonds purchased at par.

An individual muni bond may be purchased at par ($100), a premium (greater than $100), or at a discount (less than $100). Each of these coupon structures may be treated differently for tax purposes.

Par Bonds

Par bonds are the simplest for tax reporting. All of the coupon income earned during a tax year is reported as tax-exempt income. No adjustments need to be made. This amount is entered on form 1040 as tax-free income on line 8b.

Premium Bonds

Each individual security has an original cost basis. It is important to identify and remember the original purchase yield for a bond bought at a premium. This yield will be less than the coupon of the bond and needs to be calculated to at least 2 decimal places. The premium paid for the bond is amortized down each year, which reduces the basis for the bond by the amount of the amortization. This amortization is deducted from the coupon income earned and the difference is tax-exempt income earned and is entered on the 1040 line 8b. The new amortized cost basis is also used for determining capital gains and losses if the security is sold.

The logic for amortization of premium bonds:

When a bond is purchased at a premium, the coupon rate must be greater than the yield of the bond. Therefore, only part of the money the investor receives is tax-free income, and the rest is considered to be a return of his principal in the form of a coupon payment.

Amortization Calculation

Most premium bonds are amortized using a constant yield method. There are some exceptions for bonds issued before September 27, 1985. We will not discuss these exceptions in this article.

IRS Publication 550 shows how to calculate the amortization of the bond premium.

The amount of the amortization is subtracted from the coupon income which was received during the tax period. The remainder is the amount of tax-exempt interest that is reported on the Federal 1040 Return line 8b.

Example

Purchase on 1/1/05 $100,000 Salt River Project, AZ 5% coupon bonds that mature on 1/1/09 at a yield of 3.00% for a price of $107.485

Let’s calculate the tax-free interest and amortization for the first 1 year period ending 12/31/05.

The bonds mature at par so the total premium paid is $7,485 ($107,485-$100,000. To determine the bond premium amortization we multiply the acquisition cost times the purchase yield ($107,485)*(.0300) to get $3,225. We then subtract this amount from $5,000 which is the amount of coupon earned for 1 year. The result is $1,775. This is our amortization for the year.

For tax reporting purposes we would take the interest earned for the period less the amortization and report this amount as tax-exempt interest earned on line 8b of our 1040 form. This amount would be $5,000-$1,775=$3,225 for tax-exempt interest earned.

Our new cost basis would be $107,485-$1,775=$105,710.

This process would be repeated every period until the bonds mature at 100 on 1/1/09.

IRS Publication 550 (page 35)

Investment Income and Expenses

Bond Premium Amortization

If the bond yields tax-exempt interest, you must amortize the premium. This amortized amount is not deductible in determining taxable income. However, each year you must reduce your basis in the bond (and tax-exempt interest otherwise reportable on Form 1040, line 8b) by the amortization for the year.

How To Figure Amortization

For bonds issued after September 27,1985, you must amortize bond premium using a constant yield method on the basis of the bond’s yield to maturity, determined by using the bond’s basis and compounding at the close of each accrual period.

Step 1:determine your yield. Your yield is the discount rate that , when used in figuring the present value of all remaining payments to be made on the bond (including payments of qualified stated interest), produces an amount equal to your basis in the bond. Figure the yield as of the date you got the bond. It must be constant over the term of the bond and must be figured to at least two decimal places when expressed as a percentage.

Step 2: determine the accrual periods. You can choose the accrual periods to use. They may be of any length and may vary in length over the term of the bond, but each accrual period can be no longer than 1 year and each scheduled payment of principal or interest must occur either on the first or the final day of an accrual period. The computation is simplest if accrual periods are the same as the intervals between interest payment dates.

Step 3: determine the bond premium for the accrual period. To do this, multiply your adjusted acquisition price at the beginning of the accrual period by your yield. Then subtract the result from the qualified stated interest for the period.

Your adjusted acquisition price at the beginning of the first accrual period is the same as your basis. After that, it is your basis decreased by the amount of bond premium amortized for earlier periods and the amount of any payment previously made on the bond other than a payment of qualified stated interest.

The Problem: Overpaying State Income Tax

Most investors receive a year-end statement from their broker which shows how much interest was earned during the last year. The investor gives this statement to his CPA and the amount is entered on line 8b as tax-exempt interest. This can, under certain circumstances, lead to the overpayment of state income taxes. If the investor owns premium coupon bonds that are not state tax-exempt, and he has not amortized his premium, he will be overpaying his state income tax.

An Example

The investor is an Arizona resident. He owns a municipal bond portfolio that consists primarily of bonds that are premium coupon bonds. Let’s assume that 50% of these bonds are issued by municipalities in the State of Arizona, and that the other 50% are issued by municipalities that are in other states. The interest on the Arizona bonds is exempt from state taxes. The interest on the out of state securities is subject to the state tax in Arizona. Let’s also assume that the investor owns 5% coupons that he/she purchased at an average yield of 3.00%. If the investor does not amortize his coupons he will be paying interest as if he had earned a yield of 5.00%. However, if these premiums are amortized, he will pay tax on 3.00% interest. The table below shows that the investor in this case has reduced his overall yield by .05% by not properly amortizing the premiums of the out-of-state securities.

Calculating Gains/Losses

To continue with our example, let’s assume that at the end of the first year interest rates have risen 1.00% to 4.00%. We decide to take a tax loss and sell the bonds at 4.00%. What is the capital loss that we report on Form 1040 and on Schedule D?

First, we would calculate the dollar price we receive from our sale at 4.00%. The dollar price is $102.80. Thus, we receive $102,800 from our sale. We subtract this amount from our new basis which we calculated above ($105,710)-($102,800) and we get a loss of ($2,910). This is the amount we report on Form 1040 line 13 and on Schedule D.

Conclusion

It is important to remember to amortize the premiums on all holdings of municipal bonds in order to report the proper amount of tax-free interest earned, and to be able to have a proper cost-basis to calculate gains/losses on any sales of the securities. Why not then include this information as part of the year-end report for the client by including an Income Report, and Realized Gains/Losses Report that include these calculations? This will be most helpful for the client’s CPA when he does the tax return next year!

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

8:55 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Taxes

Friday, March 9, 2007

Capturing Opportunities Created By An Inefficient Market

Municipal Bonds

The Municipal Bond Market is an inefficient market. Professional money managers develop strategies to add value for their clients by taking advantage of some of these inefficiencies. Let's take a look at some of the possible ways these firms seek to increase their clients' returns with their approach to managing funds.

Inefficiencies

The Muni Market is inefficient in some of these ways:

· Smaller blocks trade cheaper than larger blocks.

· Premium bonds often trade cheaper than par bonds.

· Transaction costs are exorbitant for individuals when dealing with a brokerage firm. SEC and Journal of Fixed Income studies show the bid/ask spreads to be between 2%-2.5% for smaller pieces of Munis. These costs are significantly lower for institutions.

· Taxable munis are inherently better credits than corporate bonds, but trade cheaper than they should. For example, a AAA-rated taxable muni trades at about the same spread vs. treasuries as an A-rated corporate bond.

· There are different levels of access to new negotiated deals. For example, an institutional client has access to new deals from the manager of the issue, but competing dealers do not have access to these deals.

· Muni bonds are a legalized way around the wash-sale rule which creates a 30 day waiting period before buying back the same security.

· Shorter munis trade at lower ratios to treasuries than do longer maturities.

Strategies For Adding Value In An Inefficient Market

Strategy 1

Most Separate Account Managers consider an account to be properly diversified when they have 8-20 different holdings. A $1 million account would need block size of $50,000-$100,000 to be properly diversified. Since smaller lot size blocks of munis trade cheaper than larger lots, one possible strategy would be to buy smaller lots of bonds that fit the needs of this client. Most fixed income money managers prefer to purchase larger blocks of bonds ($1 million+) and allocate them to different accounts. The money manager that buys the smaller lots is able to generate better returns for the client because the securities are being purchased at cheaper prices.

Strategy 2

Muni bonds are primarily issued to fund long-term projects such as schools, hospitals, water, and sewers. Deals come to market with maturities from 1-30 years to fund these projects. However, there is an enormous demand in short-term munis due to tax-free money market accounts. This creates a supply/demand imbalance in the marketplace. This imbalance leads to a difference in the ratio of muni yields vs treasury yields between short maturities and long maturities. For example, today the ratio in 1 year is about 70% while it is about 89% in 30 years. In addition, the Muni Market almost always has an upward sloping yield curve. One way to take advantage of this imbalance is to "borrow short and invest long" on the yield curve. This strategy is employed by Tender Option Bond Programs (TOB's) and closed-end tax-free funds. These strategies are usually highly leveraged and are done in large size.

Conclusion

Each investor should have a strategy for his/her portfolio. Does your strategy include some way of capturing opportunities that have been created by ineffecient markets?

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

9:48 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Munis

Thursday, March 8, 2007

Finding A Way To Fund Pension Liabilities: Illinois

The Governor's Plan

Today's Bond Buyer, a trade publication, had an interesting article about the plans the governor of the State of Illinois has to fund it's $41 billion pension liability. This is his creative solution to this problem.

First, the State would sell it's state run Lottery for $10 billion by doing a Public Private Partnership (P3). This would probably be done with a long-term lease arrangement. Last year, the State of Indiana sold the Indiana Toll Road for $3.5 billion to a group of foreign investors using a 99 year lease.

Second, the State would issue $16 billion of taxable Municipal Bonds. These munis would be considered taxable because the proceeds of the bond issue would be invested in equities (a higher returning asset class). This creates an arbitrage situation which does not allow the munis to qualify for tax exemption. Illinois did what is still the largest taxable muni deal in 2003 ($10 billion) at an interest cost of 5.05%, and the pension funds have earned returns of over 14% from 2003 until now. Can they do the same with another $16 billion?

Finally, the State would raise taxes on corporations. This tax increase is expected to generate $6 billion a year beginning in 2009. The State will also enact a payroll fee on businesses that do not provide health care. This is expected to raise $1 billion a year. There are no plans to raise taxes on individuals in the Gov's plan.

Conclusion

The combination of these 3 actions is projected to get the State's pensions up to 83% funded from the current 60% funded level. Of course, this is just a trial balloon that is being floated by the governor of Illinois, Rod Blagojevich. But, in an era of unfunded pension and healthcare liabilities across the nation, it shows the general willingness to sell public assets and issue debt as a way of keeping tax increases down to as low as possible. Welcome to Public Funding 101 in America today.

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

2:22 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Credit

Wednesday, March 7, 2007

Separately Managed Accounts

Tax-Efficiency

Fixed income money managers are also able to implement different strategies for investors or RIA’s that meet the needs of their clients. This may not be the case for a mutual fund. For example, what if you are concerned that stocks might tank and so you want to have a duration target of 7,8,10.0, etc? It is practically impossible to buy a fund that will fit any duration target that you would like to have. Most fixed income portfolio managers can do this relatively easily. Another example would be an endowment fund that doesn't want money invested in what they deem to be socially offensive industries. This may be difficult by using funds, because mutual fund companies such as Pimco, Fidelity, and Vanguard all invest in tobacco or brewing bonds.

Descriptions of these benefits are shown in the table below:

Posted by

Len Templeton

at

12:21 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Munis